Learn About Radiation

The Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power plant accident Explained

WHOI senior scientist Ken Buesseler discusses the presence and effect of radiation from Fukushima on the ocean and marine life.

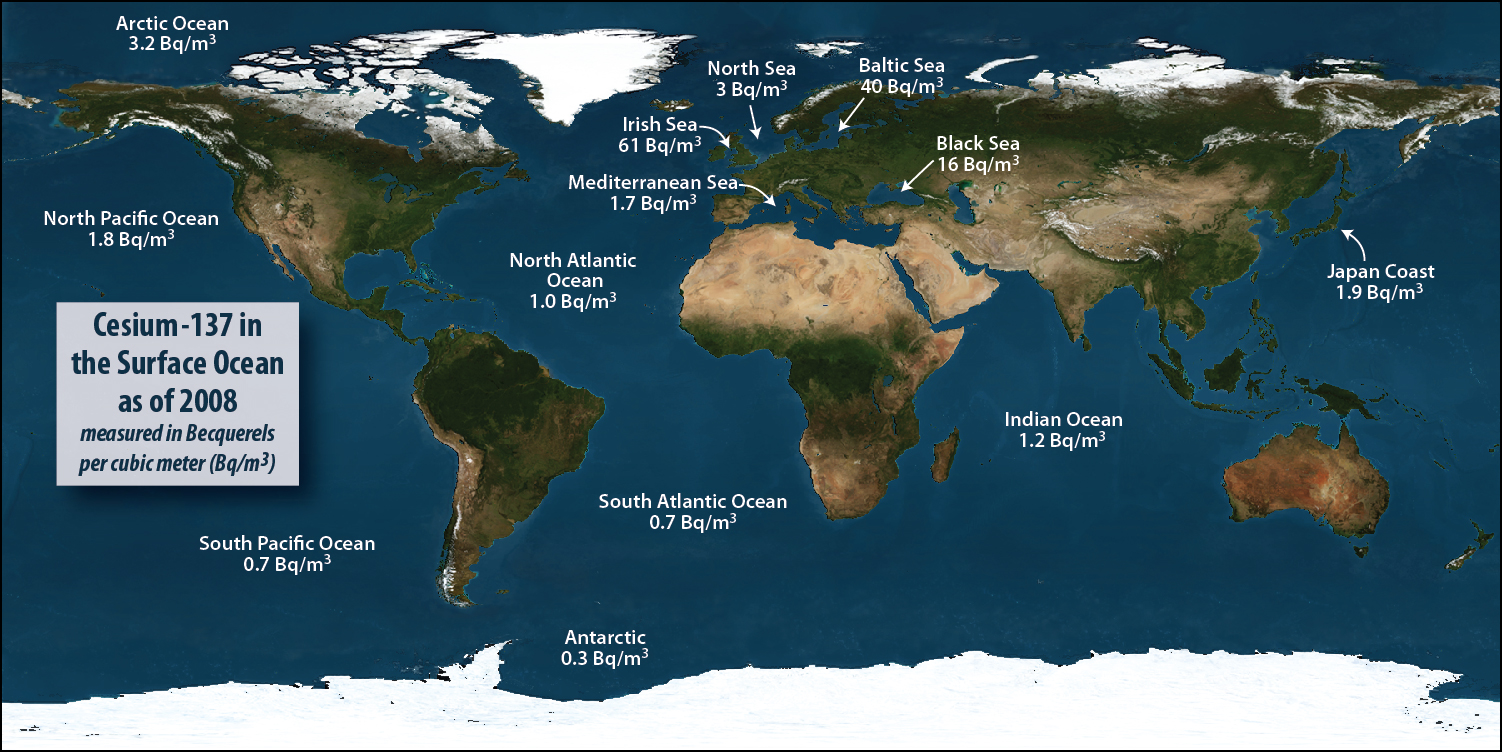

RADIATION IN THE OCEAN

The background level of radiation in oceans and seas varies around the globe. Measured in atomic disintegrations per second (Becquerels) of cesium-137 in a cubic meter of water, this variation becomes readily apparent. The primary source of cesium-137 has been nuclear weapons testing in the Pacific Ocean, but some regions have experienced additional inputs. The Irish Sea in 2008 showed elevated levels compared to large ocean basins as a result of radioactive releases from the Sellafield reprocessing facility at Seacastle, U.K. Levels in the Baltic and Black Seas are elevated due to fallout from the 1986 explosion and fire at the Chernobyl nuclear reactor. By comparison, EPA drinking water standard for cesium-137 is 7,400 Bq/m3. (Data courtesy of MARiS/IAEA and CMER; Illustration by Jack Cook, courtesy Coastal Ocean Institute, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

FUKUSHIMA PLUME PREDICTIONS

Radioactive contaminants from Fukushima are carried across the Pacific Ocean by currents, the strongest of which is the Kuroshio, and spread along the West Coast of North America by complex coastal processes. Models predict that radionuclides from Fukushima will begin to arrive on the West Coast in early 2014, mainly in the north (Alaska and British Columbia) and then move further south in coming years before appearing in Hawaii in small amounts. The concentration of contaminants is expected to be well below limits set by the U.S. EPA for cesium-137 in drinking water (7,400 Bq/m3) or even the highest level recorded in the Baltic Sea after Chernobyl (1,000 Bq/m3).

WHAT ABOUT MARINE LIFE?

Mouse over the numbers to learn more.

Radioisotopes released into the atmosphere from the Dai-ichi nuclear power plant fell into the ocean.

Water used to cool reactors flushed radioisotopes into the sea.

Microscopic marine plants (phytoplankton) take up radioisotopes from seawater around them.

Contaminants move up the food chain from phytoplankton to tiny marine animals (zooplankton), fish larvae, fish, and larger predators. Different radioisotopes are taken up at different rates by different species.

Some contaminants end up in fecal pellets and other detrital particles that settle to the seafloor and accumulate in sediments.

Some radioisotopes in sediments may be remobilized into overlying waters and absorbed by bottom-dwelling organisms.

Scientists are tracking the many pathways by which radioisotopes from the damaged nuclear reactors at Fukushima make their way into and out of seawater, marine life, and seafloor sediments. These depend on the behavior and metabolism of individual animal, the nature of complex coastal and open-ocean processes, and the physical and chemical properties of individual isotopes.

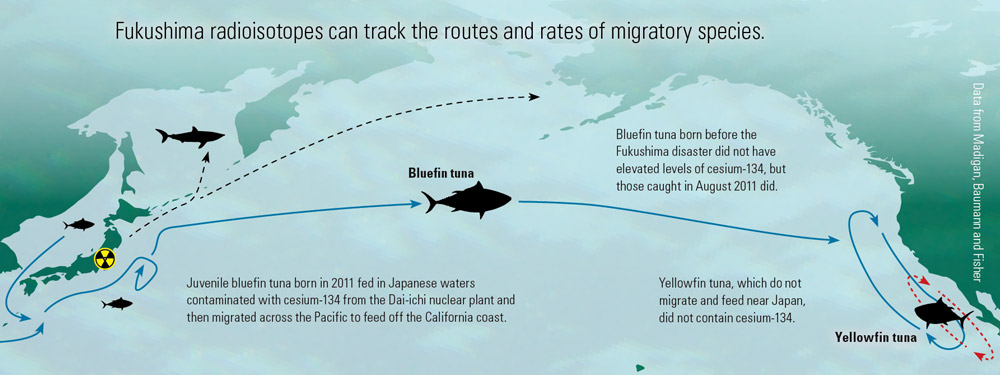

TALE OF THE TUNA

Most marine life that becomes contaminated with Fukushima radiation remains near the reactor, but some species, like Bluefin tuna, are far-ranging and even migrate across the Pacific. When these animals leave the Northeast coast of Japan, some isotopes remain in their body, but others, like cesium, naturally flush out of their system. (Credit: Madigan, Baumann, and Fisher )

SPECIAL THANKS TO: